depolitikblog.blogspot.com

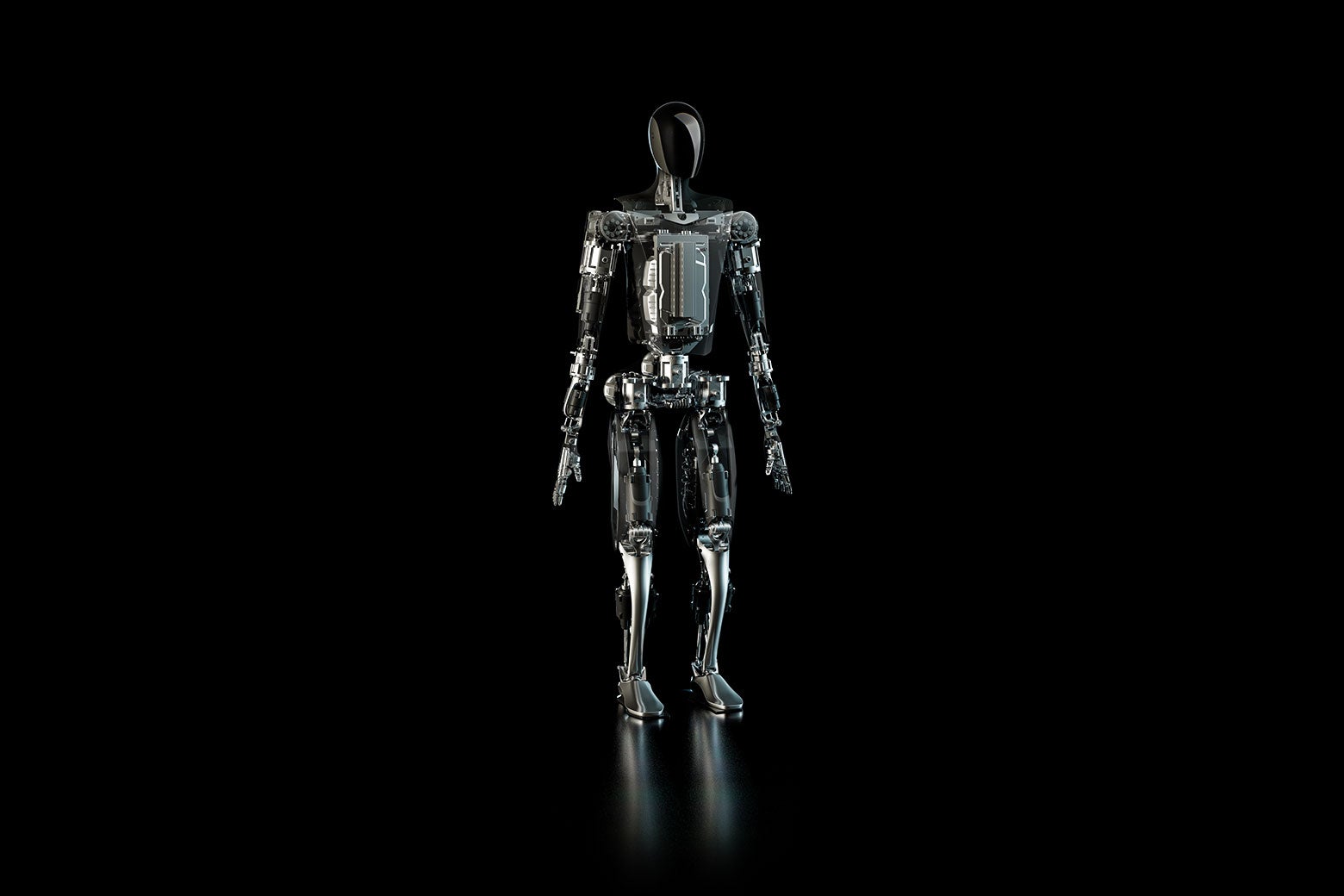

In early October, Tesla demo’d Optimus, its humanoid robot. The company’s previous demo had involved marching a human out in a robot-like bodysuit, so when Optimus walked slowly around the stage, it was met with delight from the cheering crowd. Despite the show’s futuristic framing, robotics experts were mostly underwhelmed by the reveal. Optimus’ clunky attempts at something like a dance seemed less advanced than other humanoid robots, such as Honda’s ASIMO, which played soccer with former President Barack Obama back in 2014. Tesla engineers boasted that Optimus’ hand had as many as 11 degrees of freedom (that’s to say, all the ways in which robotic parts can bend). In comparison, a robotic hand designed by a Japanese engineer back in 1963 had 27.

Despite its obviously limited capabilities, Optimus still triggered a familiar robots-will-someday-rebel-against-their-creators anxiety. What is it about Optimus that makes us feel threatened? My research on the development of Japanese robotics reveals that our feelings about robots are less about the general idea of artificiality, as many critics suggest, and more about the fact that robots are proxies for real human beings. People’s feelings toward robots often mirror their feelings toward the kind of human worker they imagine the robot is meant to replace.

Watching the long video of the demo, I was astounded to hear Elon Musk and his engineers make statements that echo what Japanese engineers said back in the ’80s (and even earlier): the need for “biologically inspired design” to create a multipurpose machine, the promise that robotic workers will liberate us from the dread of work and bring overall happiness and prosperity in 10 to 15 years, and the desire to have a robotic companion, to name a few. The experience of Japanese engineers who tried to do (some 40 years ago) what Tesla engineers are trying to do now is revelatory, both because it shows that the task is much more difficult than it seems, and also because it teaches us to identify hidden assumptions and biases that go into designing a humanoid robot.

Today, robots in Japan engender love and affection rather than fear, but this was not always the case. The pivotal moment that set Japanese robots onto the path of becoming lovable (as opposed to threatening) happened in the 1980s, when government and industry leaders sought to remedy labor shortages in the service sector by replacing humans with robots. At the time, most robots were industrial and unsuited to the service sector. For one thing, industrial robots were neither safe to be around nor able to operate in pedestrian human environments. Redesigning robots for work in public or domestic settings was difficult, but robotics engineers faced an even bigger challenge. Good service, it turns out, is not limited to effectively completing concrete tasks like cleaning, serving food, or cutting hair. As Japanese engineers discovered, it also entails emotional labor—the cheerful greetings, chitchat, and spontaneous smiles that put customers at ease. To design a robot capable of providing satisfactory service labor, robotics engineers had to do more than make advancements in A.I. or bipedal locomotion; they also had to investigate how to satisfy human users. What they found was that service robots must resemble the human workers who had formerly provided the same labor: They needed to be humanoid.

This episode in the history of Japanese robotics explains why, despite the engineering challenges of making a top-heavy machine walk on two legs, Tesla’s engineers made Optimus humanoid. In response to a question about whether future versions of Optimus will be able to “laugh at our jokes while folding our clothes,” Musk answered with a statement that could have easily come from a 1980s Japanese engineer: His goal, he said, was to create a robot that not only performs tasks but also serves as “a kind of a buddy.” Optimus’ relatively low intended retail price ($20,000, or “less than a car”) reveals that Tesla’s strategy is to create a consumer product for small, service-sector businesses, and ultimately, individual households.

The conditions couldn’t be better for such a product. The pandemic has decimated the service-sector labor force. Understaffed restaurants close earlier and serve fewer people. Some fast-food chains are considering a move to drive-through service only. Airports are a giant mess. All because many humans are no longer willing to tolerate poor working conditions for unlivable wages. Replacing them with service robots would definitely pay off for an enterprising employer if—and it is a big if, given that Optimus had to be manually wheeled off stage—robotics engineers can make their humanoid machines do what is expected of actual humans. (In Japan, for example, “job-holding” robots are still effectively a gimmick—a host of humans do the labor and/or maintain the robots, and the robots themselves are crowd-pleasing, rather than labor-saving, devices.)

Robots reveal what we expect of those who serve us and where these expectations come from. In my research, I’ve found that robotic designs contain cognitive cues that resonate with users’ previous experiences. Robots are not modeled on a “generic” human being, but on a specific kind of human who provides a specific kind of labor. Robotic design, in other words, doesn’t just reflect the tasks we would like the robot to do, but the kind of human we would expect to do them. Design details of a given humanoid robot reveal hints about the kind of human worker engineers imagined (even unconsciously) as a model. These design details can tell us a lot about perceptions of the actual people associated with a particular labor, as well as tacit assumptions about status and identity. Most importantly, the design of humanoid robots reveals something of how we feel about service laborers and how we believe they “should” behave.

In the case of Japanese androids, service robots are often diminutive and feminized (with a tiny chin and nose, no jaw line, and a high-pitched vocal range). The design of their bodies offers visual hints to the kind of humans they are meant to replace. The subtle apron visible on some Japanese service robots, for example, is associated with the caring “auntie.” These robots are expressly designed to give the user a sense of family sympathy, of being taken care of, of being important. In contrast, robotic “receptionists” are modeled on hypersexualized young women, a design that communicates that the labor expected from them is not strictly clerical. (Sexbots are another story—and the reason that Japanese engineers have worked so hard to develop super realistic artificial skin.)

That brings us back to Optimus. Musk stated that it was possible “to put all kind of costumes on the robots.” So, what does Optimus’ design—as opposed to the drawn prototype or the man in the suit who modeled it—reveal about the kind of person it (or, as the designers would have us believe, “he”) is dressed as? First, he is undeniably male, with a tall stature, exaggerated quads, and broad shoulders. Optimus’ tiny head telegraphs that he is not a thinker. The blank slate where one might expect a face assures us that his emotions do not matter. The design tells us that the human worker Optimus is modeled on is valued for his manual labor alone. He does not think. He labors. He does what is asked.

It’s also worth noting that, in the demo, Optimus’ face and hands are black. Does that mean anything? Perhaps. Many American users may (sometimes unconsciously) still make a connection between male manual labor and Blackness. I once read the transcript of a conversation between Japanese engineers, who, in 1973, reflected on their belief that America sought to design robots in order to replace its Black labor force. I have no doubt that Japanese engineers were reading American magazines, where robots were imagined to take over jobs often associated with Black Americans—hard manual labor, manufacturing, and trash collection. And some American articles are even more explicit about their intentions. My colleague Jason Resnikoff cites a 1957 article from Mechanix Illustrated that promises readers that they “will own ‘slaves’ by 1965.” That is, “robotic” slaves—robotic butlers, cooks, drivers, cops, secretaries, and security guards. Optimus could thus be interpreted as a representation for both oppressive labor structures and the racialization and subsequent devaluation of different kinds of labor. The fear Optimus evokes among some Americans, perhaps, is a fear of rebellion against those structures.

Design is not neutral. Robotics engineering reflects what we want in a worker, and in turn, what we want for ourselves. While Japanese robots embody a desire to be served with love by someone who gives more than she demands in return, Optimus embodies an obedient laborer.

I am not afraid that robots will take over the world. The distance between what robots can do now and what they would need to be able to do to take over the world is much greater than most imagine. But I am afraid that robots like Optimus will eventually bring harm to humans. They will do so not by injuring humans physically, but by offering a false hope for technological fixes that would magically solve social problems. Even more devastatingly, without mindful attention to design, humanoid robots will inevitably reinforce harmful associations attached to race, gender, and subservient labor, and thus exacerbate the discrimination and exploitation of human beings. Algorithms can be biased; social networks can be biased, too. And so can robots.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

Adblock test (Why?)

"Demo" - Google News

October 24, 2022 at 10:45PM

https://ift.tt/Ygnb2Qw

Elon Musk Optimus demo: What Tesla's design decisions tell us about robotic bias. - Slate

"Demo" - Google News

https://ift.tt/qeD107y

https://ift.tt/wJDs9fR